By Ed Offley

Just how dangerous is the water?

Between January 1 and July 8, the city Beach Rescue service posted either single or double red warning flags on 116 days, marking 61 percent of the 190 days of that time span. Double red flags mandating closure of the Gulf of Mexico to swimmers flew on 44 days, while single red flags – cautioning swimmers of potentially deadly rip currents – flew on 72 days.

“Waves aren’t killing people here. Waves aren’t the hazard,” said Daryl Paul, Beach Rescue director for Panama City Beach. “It’s rip currents that are the hazard, and that’s what we’re flying the flags for.”

“Waves aren’t killing people here. Waves aren’t the hazard,” said Daryl Paul, Beach Rescue director for Panama City Beach. “It’s rip currents that are the hazard, and that’s what we’re flying the flags for.”

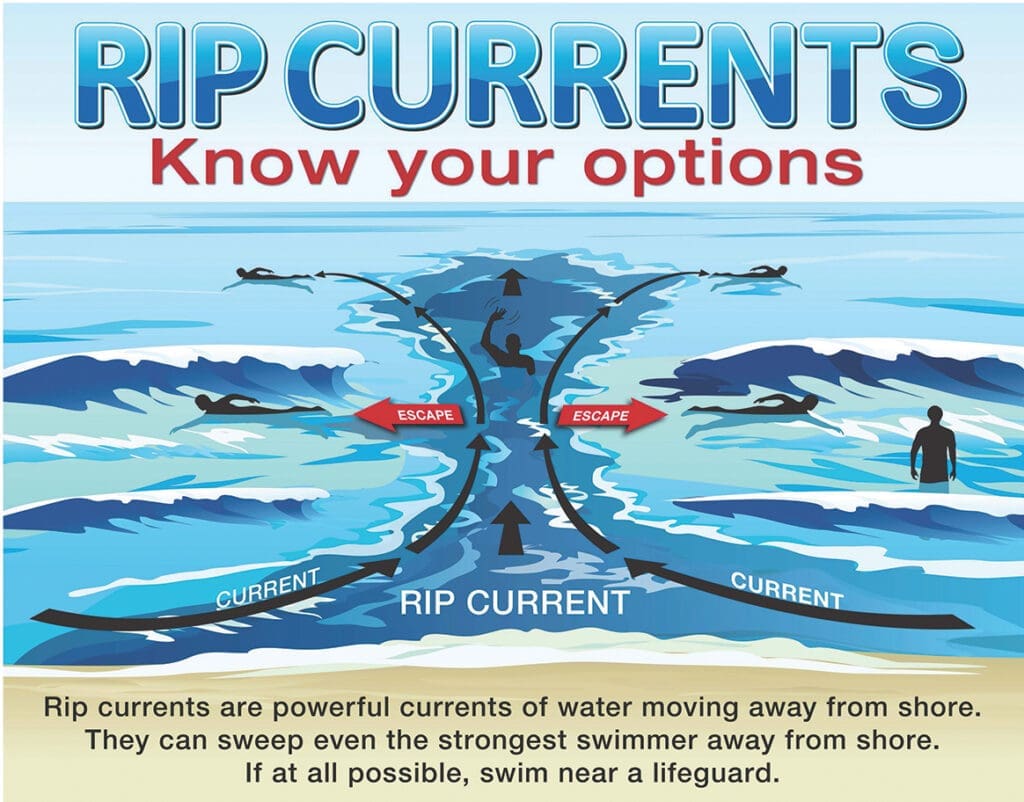

Rip currents are rapidly moving channels of water that pour outward from the beach, Paul explained. They are created when long Gulf swells break in the surf zone and pile up greater amounts of water than normal. The fast-moving currents can trap even the most experienced swimmer and sweep him or her away from the shoreline into deeper water. This can lead to a swimmer panicking and attempting to fight the current, leading to exhaustion and the threat of drowning.

Experts say if you get caught in a rip current, you should not fight it, but instead, keep calm and swim parallel to the shore until you break free, Only then is it safe to swim back to the beach.

Common misperceptions among inexperienced swimmers are that rip currents pose a threat only during high surf conditions. “While rip currents are powered by wave action,” Paul told a City Council workshop on beach safety July 11, “there is still water moving even when the [surface of the Gulf] is flat.”

Common misperceptions among inexperienced swimmers are that rip currents pose a threat only during high surf conditions. “While rip currents are powered by wave action,” Paul told a City Council workshop on beach safety July 11, “there is still water moving even when the [surface of the Gulf] is flat.”

After becoming director of beach safety operations, Paul updated the criteria used to determine which beach warning flag to fly. In addition to visually observing surf conditions, Paul consults both the sun and moon tables for indications of higher-than-normal tides; checks in with neighboring beach safety operations along the Florida Panhandle, and obtains data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for potential shifts in the weather and Gulf currents.

The refined methodology – and not a worsening of surf conditions – has led PCB Beach Rescue to fly single and double red flags more frequently than in past years, Paul said. “Our methodology – we’ve improved it.”

Meanwhile, the Bay County Tourist Development Council has expanded the use of social media to immediately inform visitors and residents alike of a change in the beach warning flags – especially when conditions warrant deploying either single or double red flags.

Asked at the Council workshop if any one particular area of the nine-mile beachfront is particularly hazardous, Paul said rip currents occur “anytime, anywhere.”

Last year, about 91 people died in rip currents nationwide, according to the National Weather Service data. That was up from the 10-year average of 74 deaths per year.